This was a very popular post from April, 2012. The data is pretty much the same. And it bears repeating.

Managers and supervisors (especially in the Baby Boomer cohort) in almost every type and size of business have been known to lament the lack of loyalty and so-called business savvy in the Millennial generation.

- “They want to be promoted too fast!”

- “They don’t want to pay their dues!”

- “They don’t understand how things work!”

- “They want too much flexibility!”

- “When things don’t go their way they quit!”

- “Why won’t they stay?”

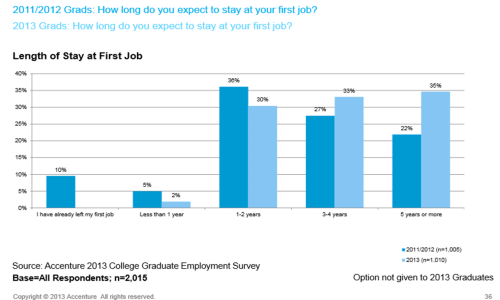

The bottom line is that organizations are finding it challenging to keep Millennials engaged and on the payroll. In fact, with the average employment tenure of workers in the 20-24 year -old age group at 1.5 years (per the BLS), it’s challenging to keep all our employees engaged and the on the payroll. (See my previous post on the Quits vs. Layoffs gap. It might not be what you think!)

Achievers and Experience Inc. fielded their annual survey of graduating college students in January. The data are eye opening.

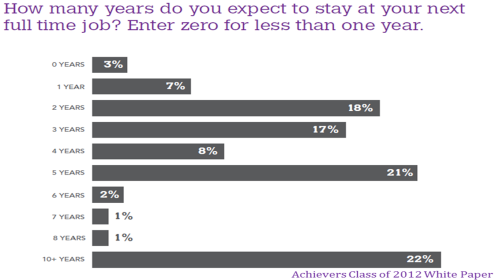

Despite what we think we know about them, the vast majority of these about-to-enter-the-workforce Milllennials would really like to stay with their next (in most cases, first) employer for 5 years or longer! Wait. What? Look at the chart below:

47% of the 8,000 college graduating respondents in the Achievers/Experience Inc. survey indicated that they expected to stay with their next employer five years or longer. Note the language: expect to stay not would like to stay! That means when they join our organizations they have every expectation of making a career with us. They’re not just accepting a job. They’ve evaluated our EVP (Employer Value Proposition) as a match for the meaning they want to create in their lives through their work. (Interesting to note that the biggest percentage of respondents expect to stay with their employer for 10+ years!)

So, OK. This has got to be their youthful exuberance and relative inexperience speaking, right? Well, I wonder if that really matters.

Employers need these Millennials. Employers need these Millennials now. Employers will need these Millennials more every day. (See my recent post here.)

And employers need them to stay a whole lot longer than 1.5 years!

So what happens between “I expect to stay with my employer for 10 or more years…” and “…after one year with the organization I’m leaving for a better opportunity”? I think we all know that answer to that question.

We don’t live up to the EVP we sold them. We don’t engage Millennials the way they tell us they want to be engaged. Instead, we…

- make sure they fit into our existing career paths and job descriptions

- focus on making sure they “pay their dues” – the way we did

- keep our processes and rules rigid and unbending – and only pretend to listen when they offer up “different” ways of working

- resist the notion that work can be done with excellence anywhere but in a cubicle

- make it difficult for Millennials to interact with senior leaders

- make it difficult for Millennials to collaborate with colleagues

- designate social responsibility activities a perk instead of a foundational value

- try to “lure” them to stay with tenure-based plaques and timepieces

These data are a wake-up call for employers. It’s a message from our talent pipeline that they really do want to engage with us; they believe our employer brand marketing messages; they want to learn and grow with us.

It’s time to listen harder and make sure our employer brand messages aren’t experienced as bait and switch tactics.

I don’t know about you, but I’d hate for the Millennials to have such negative employment experiences at the beginning of their careers that they opt out of organizational life altogether before they’re 30. We’d really be in a pickle then!

As we prepare to attract, develop and retain skilled workers around the world, who works and who doesn’t work is interesting to me. So I thought I’d share the following charts that I ran across in a

As we prepare to attract, develop and retain skilled workers around the world, who works and who doesn’t work is interesting to me. So I thought I’d share the following charts that I ran across in a